Statistician and Black Swan author Nassim Taleb said “if you gave an investor the next day’s news 24 hours in advance, he would go bust in less than a year.” Taleb is implying that even with an informational advantage, investors must properly manage their risk. The feeling of having an edge, be it real or perceived, tends to lead investors to overconcentrate their bets. This type of behavior has been shown in behavioral experiments with simple mathematical solutions. In one study,[1] participants were given a biased coin with a 60% chance of a flip landing on heads. They were given $25 and were able to bet any size and configuration for thirty minutes. They would also be able to pocket any winnings, subject to a cap of $250. Given the large probabilistic advantage, the researchers expected the participants to do reasonably well. As Nassim Taleb probably would have expected, the results were shockingly underwhelming with 28% of participants going bust and 67% betting on tails at least once. With no upper limit on the amount one could win, 300 flips with the optimal bet size could have yielded an astonishing value of over $3 million in this game. Why did so many participants fail to earn anything and what could they have done differently to convert their advantage into wealth?

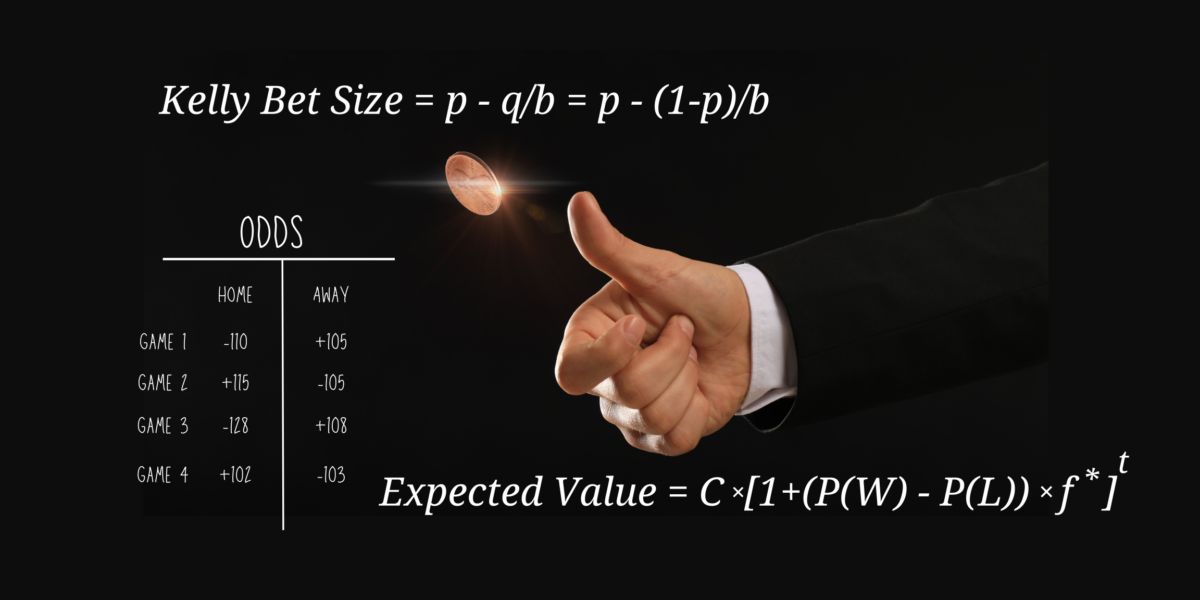

The aforementioned study is ultimately a challenge related to bet sizing. Mathematically, the optimal bet size for this problem is 20% of each participant’s “wealth.” This can be derived from the Kelly Criterion. The Kelly Criterion is a well-known formula for determining optimal bet size developed in 1956 by John L. Kelly, a scientist at AT&T Bell Laboratories. For a bet like a coin flip, where a negative outcome amounts to a total loss on the bet, the Kelly position size can be given by:

Kelly Bet Size = Probability of a Win – Probability of a Loss/ Fraction of Bet Gained with a Win

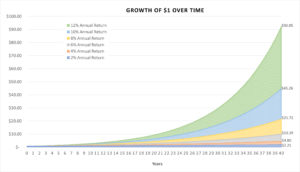

The expected value in this biased coin flip example is 0.6-0.4/1 = 0.2 on every dollar bet, or 20% of available wealth. The researchers point out that repeatedly betting a fixed 20% size gives a 95% chance of reaching the maximum payout of $250. Yet they found that participants frequently gambled everything on one bet and one third of participants ended with less money than they started with. This experiment shows that decisions around the allocation of funds are often sub-optimal. Heuristics like the Kelly Criterion can help investors to make rational decisions around position sizing and capital allocation.

The coin flip example is fairly straightforward: you have an advantage in knowing that heads is weighted to occur 60% of the time, and the payout will always match your bet, no matter which side you take. Thus, a rational player would always bet on heads, and with the correct position sizing, would have a fairly good chance to make substantial sums of money. Unfortunately, the real world is not so advantageous. Consider a pastime that has recently exploded in popularity due to regulatory changes: sports betting. Here, individual gamblers have no particular edge. In fact, they actually have a slight disadvantage since the sportsbook has to have their cut of the profits. To illustrate, we can examine the recent big football game between the Kansas City Chiefs and the San Francisco 49ers. Avid football fans already know the Chiefs won this game, but prior to the game, the odds had the 49ers favored at -128 and the Chiefs as underdogs at +108 according to CBS Sports. This strange notation simply relates to the profit received from a winning bet. To bet on the Niners and receive a $100 profit, bettors would need to wager $128. A $100 bet on the Chiefs would yield a profit of $108 in a Chiefs win. These payouts are based on probabilities which can be calculated as:

Implied Probability of a Win = Capital Risked/(Capital Risked + Potential Profit)

In this case, the implied probability of a 49ers win was 128/(128 + 100) = 56.14%. The probability of a Chiefs win was 100/(100 + 108) = 48.08%.[2] Using the Kelly Criterion with the market implied odds, the optimal bet size on the 49ers would be… 0%. Would a rational person bet on the 49ers then? The answer is: maybe. Suppose a person with superior football expertise who has performed deep analysis on the teams comes up with a 59% probability of the 49ers winning. With this increased win probability, our hypothetical gambler has an edge over the odds that the betting market is giving him. The Kelly Criterion now says that this gambler should bet 6.5% of his total capital on the 49ers. Of course, this presents two problems. First, our gambler could very well be wrong on his probability assumptions. That is, is he really smarter than the overall betting market? Second, as we now know, the Chiefs won. Despite a bet on the Niners being entirely rational, assuming our gambler’s probability estimates are correct, we are still dealing with probabilities. There is still a 41% chance that the bet will lose. This is why position sizing is so important. By only risking 6.5% percent of capital, our gambler can survive to keep making more bets and have a chance to gradually compound his winnings.

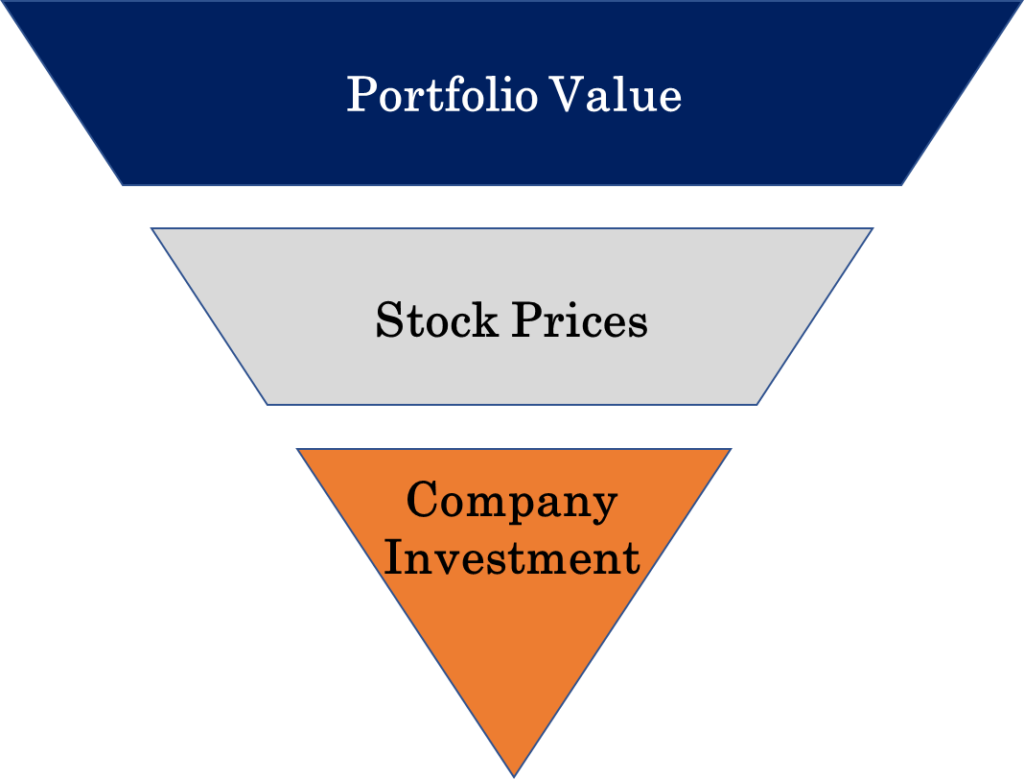

With this backdrop, there are several takeaways from these examples that can be applied to investing in financial markets. The first is that investing is a zero-sum game, much more closely represented by the sports betting scenario than the coin flip example. When an investor purchases an asset, there is always another party across the table selling the asset, similar to betting on the other team. Like sports betting, the asset will be priced according to market expectations. A rapidly growing company with solid underlying fundamentals will very likely trade at a higher valuation compared to a distressed company on the verge of bankruptcy. In financial theory, a higher valuation implies a lower expected return in the future. Conversely, a lower valuation would portend a higher expected future return. Of course, those return expectations come with extreme differences in risk. Investors are compensated, or given a premium, for taking on risk. What sort of payoff would you require to bet on the local high school junior varsity football team versus the 1985 Chicago Bears?[3]

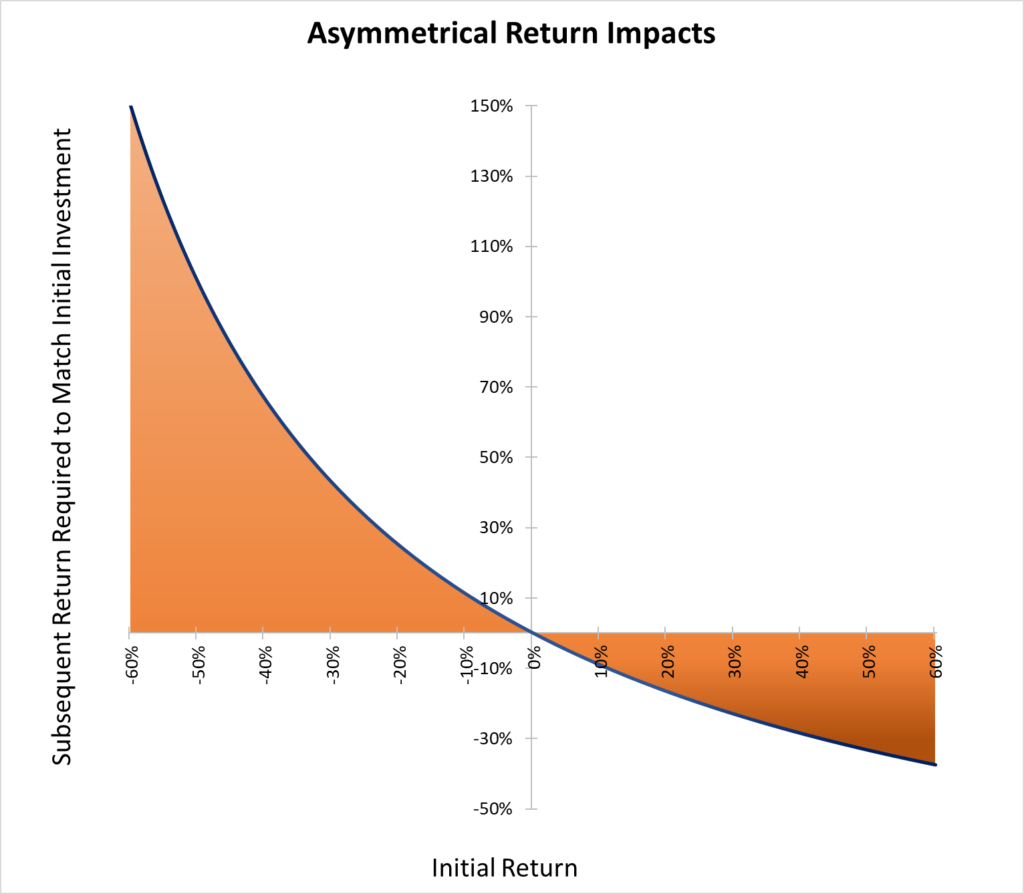

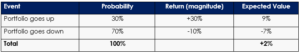

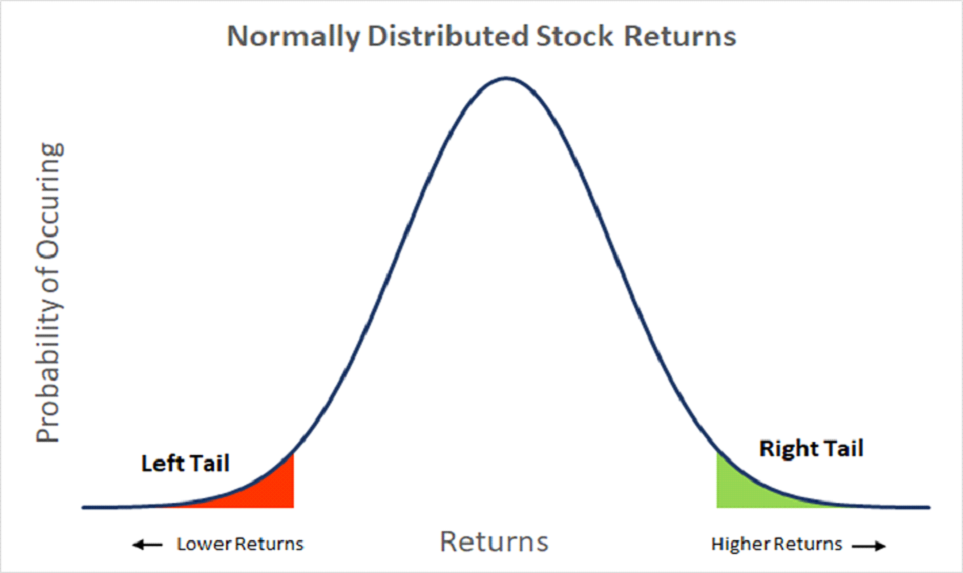

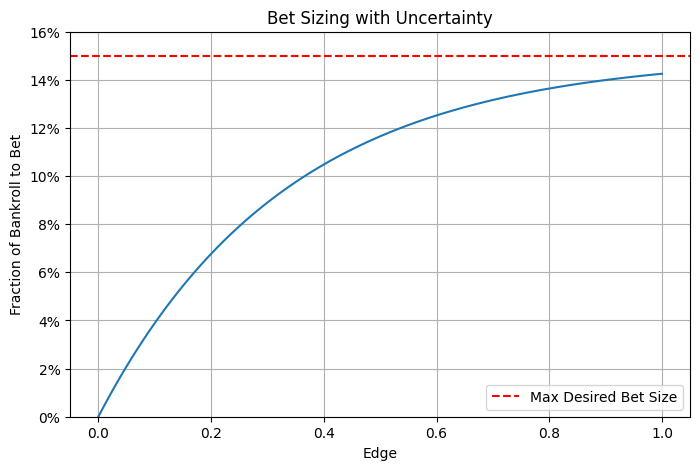

A second takeaway is that the ability of investors to consistently outperform the markets ultimately depends on their ability to examine outcomes not in terms of certainties but in terms of probabilities, and investors must be able to convert those probabilities into rational position sizes given that financial markets contain high levels of uncertainty. Even the sports betting example above is ultimately too simplistic as it focuses on a single estimate of probability. Investors must instead recognize that outcomes are not binary; there are numerous scenarios which could play out, each with their own likelihood of being realized. When you add this uncertainty, the optimal bet size likely becomes smaller and begins to level off for larger bet sizes.

A hypothetical example with non-linear bet sizing. As the bet size becomes larger, the increase in bet size becomes smaller. In this case, the individual does not wish to bet more than 15% of capital on one bet, no matter the advantage they have (or think they have).

The final key takeaway is that investors must be aware of potential biases which could affect their decision-making. For example, in the example of the hypothetical gambler who believes his estimates are more accurate than the odds given by sportsbooks, one must ask if the gambler actually has an edge or if he is overconfident in his abilities. There is a reason the famed psychologist and Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman called overconfidence “the most significant of the cognitive biases.” Similarly, it is challenging to beat the stock market consistently. Having a rigorous investment process in place can help to instill discipline and avoid overconcentrating in too few positions.

An additional bias that could impact position sizing is loss aversion. The Kelly Criterion, for example, will give a rational position size for risk-neutral investors, but in reality, most investors are risk averse. This means losses have a larger psychological impact than gains. Suppose the Kelly Criterion indicates optimal position sizing of 20% of wealth. Someone starting with $100 may be very willing to risk $20, but an investor with $500,000 may not be willing to risk a daunting $100,000 on a single trade. For this reason, it is common to see traders use a fraction of the optimal Kelly bet size to make the volatility more tolerable.

Ultimately, investors must consider expectations of both risk and return before translating investment opportunities into potential positions. Furthermore, systematically applying a heuristic such as the Kelly Criterion can help to determine appropriate position sizes, but the overall portfolio must also be a consideration. By just applying the Kelly Criterion to individual positions, the portfolio may be taking on much more risk than intended if the positions are highly correlated. Position sizing is a key driver of portfolio returns, and it is essential to ensure positions are sized not only to take full advantage of solid opportunities when they arise but also to ensure portfolio survival in the long run.

[1] Haghani, Victor and Dewey, Richard, Rational Decision-Making under Uncertainty: Observed Betting Patterns on a Biased Coin (October 19, 2016).

[2] Note that the sum of the alternative win probabilities exceeds 100% since the bets are priced to make money for the sportsbook, no matter who wins.

[3] The ’85 Bears are widely regarded as one of the best NFL teams of all time, scoring 456 points while only allowing 198 according to ESPN.

The views expressed represent the opinion of Passage Global Capital Management, LLC. The views are subject to change and are not intended as a forecast or guarantee of future results. This material is for informational purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice and is not intended as an endorsement of any specific investment. Stated information is derived from proprietary and nonproprietary sources that have not been independently verified for accuracy or completeness. While Passage Global Capital Management, LLC believes the information to be accurate and reliable, we do not claim or have responsibility for its completeness, accuracy, or reliability. Statements of future expectations, estimates, projections, and other forward-looking statements are based on available information and Passage Global Capital Management, LLC’s views as of the time of these statements. Accordingly, such statements are inherently speculative as they are based on assumptions that may involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Actual results, performance or events may differ materially from those expressed or implied in such statements.